Prime Magazine (12 June 2024)

Urinary incontinence, the involuntary leakage of urine, can affect people of all ages, including the younger population. However, it is more commonly reported in women and those over 50. Various factors can contribute to incontinence. Age, constipation, increased body mass index (BMI), urinary tract infection and impaired physical function are common factors for both women and men. In women, factors like pregnancy and postpartum can strain, stretch and weaken the pelvic floor muscles (PFMs), while menopause or a history of hysterectomy can also contribute to urinary incontinence. For men, surgery for prostate cancer or benign prostate disease can increase the risk.

Management

There are several ways to manage urinary incontinence. The current evidence-based practice and management approach includes:

- Behavioural and lifestyle modifications;

- PFM training;

- Pharmacological intervention; and eventually

- Surgical intervention (for individuals experiencing incontinence symptoms who do not respond to previous management options)

Lifestyle Modification

Lifestyle modifications include reducing the consumption of drinks that can irritate the bladder lining, such as carbonated beverages, alcohol or caffeinated drinks (e.g. coffee and tea).

This irritation can lead to increased urinary frequency and urgency. It is also important to reduce overall fluid intake, especially in the evening, between dinner and bedtime, and to avoid drinking fluid two hours before sleep to reduce the frequency of urinating in the middle of the night. Research has shown that repeatedly waking up during the night over the long term may cause disturbed sleep, eventually affecting one’s quality of life and general health.

Behavourial Modification

Behavioural training plays a vital role in reducing urinary incontinence rates. Habits like using the bathroom “just in case” (e.g. going before leaving the house or passing by a toilet) may affect normal bladder function. Such behaviour trains the bladder to operate at a lower capacity over time, leading to increased urgency and frequency of urination. A healthy bladder can hold around 400-600ml of urine, and most people urinate 4-6 times a day or every 2-3 hours, with 0-1 nighttime trip. Generally, a person’s daily water intake is around 1,500-2,000ml, roughly 30ml per kilogram, depending on body size.

To retrain or reset your bladder, you can try to ignore the first urge and hold for another minute, gradually increasing the holding interval over time. Some urge suppression strategies include PFM contraction and deep breathing, which aim to reduce the urgency to urinate, giving you more time to reach the toilet and prevent leakage. Rushing to the bathroom may increase the urgency to void, given the increased intraabdominal pressure that applies more pressure on the bladder. Additionally, crossing your legs and attempting to distract yourself with other tasks may help you to control your urge to urinate.

PFM Training

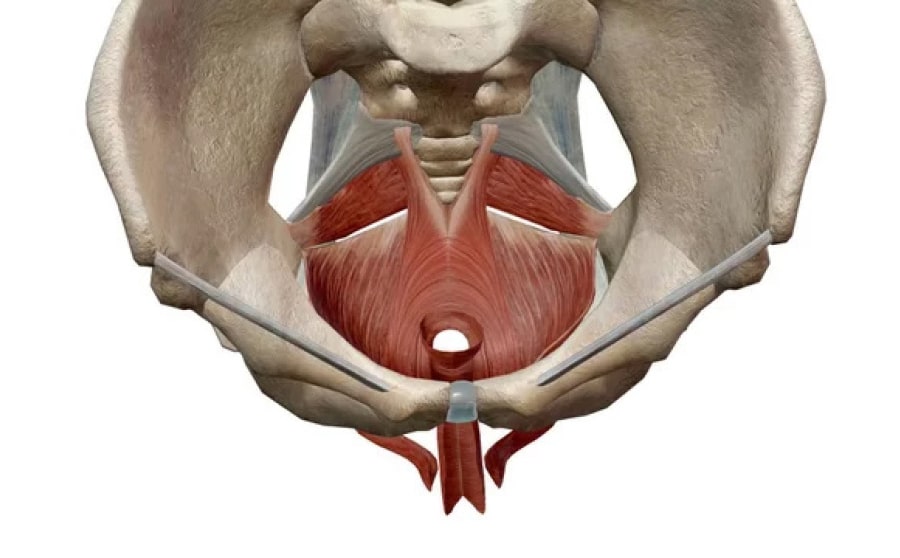

PFM training is important in managing stress, urge or mixed urinary incontinence. It can be done alone, with a manual technique or with a biofeedback device. The PFMs are a group of muscles and connective tissues that extend like a sling across the base of the pelvic, and have a crucial role in supporting the pelvic organs. They play an integral role in urinary, defecatory and sexual function. Similar to other strengthening exercises, PFM training can help to improve the strength, endurance and timing of the contraction of the PFMs to help manage urinary incontinence.

The pelvic floor muscles (in red) are located between the tailbone and the pubic bone within the pelvis. Photo Credit: Adobe Stock

The pelvic floor muscles (in red) are located between the tailbone and the pubic bone within the pelvis. Photo Credit: Adobe Stock

PFM training involves lifting and holding, followed by releasing the PFMs, without contraction of other muscles such as the hip adductors and gluteal muscles. There are some facilitation techniques for PFM, such as “imagining you are pulling a string up through the vagina and out through the belly button” and “having the sensation of stopping yourself passing wind or urine”. Continue to breathe normally when doing PFM exercises.

Pelvic floor muscle training can be done in crook lying (right), sitting (left), standing and other functional positions as a form of progression. Photo Credit: Tan Tock Seng Hospital.

Pelvic floor muscle training can be done in crook lying (right), sitting (left), standing and other functional positions as a form of progression. Photo Credit: Tan Tock Seng Hospital.

It is important to conduct both strength and endurance training for PFM. Strength training is characterised by low repetitions and high loads to improve muscle strength and tone. The load for PFM training can be managed by increasing the contraction effort each time or by progressing the position when performing PFM contraction, from lying (figure 2) to moving to sitting (figure 3), standing, squatting or other functional positions.

Endurance training involves higher repetitions or increased PFM contraction duration with low to moderate loads. According to recent research, such PFM training is recommended for three sets of eight to twelve repetitions a day, and each contraction should be sustained for eight to twelve seconds each. These are general guidelines for the exercise programme, as the intensity of the exercise can be varied according to the individual’s profile. If you are in doubt or wish to have individualised guidelines, do seek professional advice.

Pharmacotherapy and Surgery

For those who do not respond to the above approaches, pharmacotherapy may be considered. Medications can help to relax the bladder muscle and increase the amount of urine the bladder can hold. It can also help to reduce the signals sent to the brain that trigger bladder contractions. Surgery, such as sling procedure, colposuspension and artificial urinary sphincter, may be recommended for patients who do not respond to non-surgical treatments.

Summary

Urinary incontinence is a common issue affecting people of all ages, especially older adults, and it can significantly impact one’s quality of life and general health. Understanding the different types of urinary incontinence is important for effectively managing the condition, allowing for tailored treatment approaches that address individual needs. Treatment may encompass lifestyle modifications, behavioural training, PFM training, pharmacotherapy and surgical intervention. Combining PFM training with other behavioural strategies can effectively alleviate symptoms, reducing leakage episodes or the number of continence pads used.